Since the election on November 5th, many Democrats across the country have been asking themselves one question: what happened? The presidential election was essentially over by 3:00 a.m. on November 6th, when the Associated Press formally called Pennsylvania for Trump, who ended up winning every swing state and the popular vote. So what did happen? Here is an overview of how my model differed from the actual election results and why that might be.

A Refresher

In case you missed it or need a refresher, my model predicted a 270-268 Harris victory in the Electoral College and a 49% to 48% Harris victory for the national popular vote.

My national popular vote model used LASSO to select from a large number of potential predictive variables and ended up using a series of eight: percent of the country identifying as independent, the change in party identification for either party from the year preceding the election, vote share from the previous election, and five different weeks of polling, including the week just prior to the election.

I made two separate models for predicting the electoral college, one for states with significant polling aggregate data on FiveThirtyEight, and one for those without. Predictive variables for both models included: state-level lagged vote share for the two prior elections, whether the candidate is a member of the incumbent party, national Q2 GDP growth, average state-level unemployment, the change in partisan identification for either party from the last election, and state fixed effects. For states with polling aggregates, the mean polling average and latest polling average were included in my model.

Below is a breakdown of my predictions for each state.

| State | Lower Bound | Prediction | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 25.22 | 34.47 | 43.71 |

| Alaska | 30.58 | 39.83 | 49.07 |

| Arizona | 44.58 | 48.33 | 52.08 |

| Arkansas | 25.99 | 35.24 | 44.48 |

| California | 57.18 | 60.93 | 64.68 |

| Colorado | 52.86 | 56.61 | 60.36 |

| Connecticut | 46.20 | 55.44 | 64.68 |

| Delaware | 45.75 | 54.99 | 64.24 |

| Florida | 41.86 | 45.61 | 49.36 |

| Georgia | 44.56 | 48.31 | 52.06 |

| Hawaii | 49.84 | 59.08 | 68.33 |

| Idaho | 19.00 | 28.24 | 37.48 |

| Illinois | 45.56 | 54.80 | 64.05 |

| Indiana | 29.33 | 38.58 | 47.82 |

| Iowa | 33.00 | 42.24 | 51.48 |

| Kansas | 28.71 | 37.96 | 47.20 |

| Kentucky | 23.01 | 32.25 | 41.49 |

| Louisiana | 29.83 | 39.07 | 48.32 |

| Maine | 51.92 | 55.67 | 59.42 |

| Maryland | 60.34 | 64.09 | 67.84 |

| Massachusetts | 60.21 | 63.96 | 67.71 |

| Michigan | 47.45 | 51.20 | 54.95 |

| Minnesota | 48.55 | 52.30 | 56.06 |

| Mississippi | 30.24 | 39.48 | 48.72 |

| Missouri | 39.49 | 43.24 | 46.99 |

| Montana | 35.28 | 39.03 | 42.78 |

| Nebraska | 34.25 | 38.00 | 41.75 |

| Nevada | 45.25 | 49.00 | 52.75 |

| New Hampshire | 47.74 | 51.49 | 55.24 |

| New Jersey | 44.70 | 53.94 | 63.19 |

| New Mexico | 48.84 | 52.59 | 56.35 |

| New York | 52.89 | 56.64 | 60.40 |

| North Carolina | 43.28 | 47.03 | 50.78 |

| North Dakota | 17.60 | 26.85 | 36.09 |

| Ohio | 41.05 | 44.80 | 48.55 |

| Oklahoma | 20.31 | 29.55 | 38.79 |

| Oregon | 42.64 | 51.88 | 61.12 |

| Pennsylvania | 46.41 | 50.16 | 53.91 |

| Rhode Island | 48.15 | 57.39 | 66.64 |

| South Carolina | 31.66 | 40.90 | 50.15 |

| South Dakota | 19.37 | 28.61 | 37.86 |

| Tennessee | 27.13 | 36.37 | 45.61 |

| Texas | 41.22 | 44.97 | 48.72 |

| Utah | 23.29 | 32.54 | 41.78 |

| Vermont | 49.58 | 58.82 | 68.07 |

| Virginia | 48.19 | 51.94 | 55.69 |

| Washington | 53.97 | 57.72 | 61.47 |

| West Virginia | 21.25 | 30.49 | 39.74 |

| Wisconsin | 46.82 | 50.57 | 54.32 |

| Wyoming | 15.13 | 24.37 | 33.61 |

Notably, the swing state breakdown for my predictions was that Harris would win Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, while Trump would win the rest.

Assessment of Accuracy

The confusion matrix below shows how my predictions for each state compared to the actual election results.

## Prediction

## Actual DEM REP

## DEM 19 0

## REP 3 28

I correctly predicted 28 states to go to Trump and 19 to go to Harris. I only got three states wrong, which I predicted to go to Harris, but actually went to Trump. Unfortunately those states were the key swing states of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which decided the outcome of the election.

Here’s a further breakdown of every state, and it’s prediction, true outcome, and error. Positive errors show an error in favor of Harris, and negative for Trump.

| State | Prediction | True Value | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vermont | 58.82 | 66.39 | -7.56 |

| Utah | 32.54 | 39.41 | -6.87 |

| South Dakota | 28.61 | 35.05 | -6.44 |

| Oregon | 51.88 | 57.30 | -5.42 |

| North Dakota | 26.85 | 31.28 | -4.43 |

| Kansas | 37.96 | 41.78 | -3.82 |

| Idaho | 28.24 | 31.24 | -3.00 |

| Oklahoma | 29.55 | 32.53 | -2.98 |

| Hawaii | 59.08 | 61.79 | -2.71 |

| Delaware | 54.99 | 57.48 | -2.49 |

| Alaska | 39.83 | 42.15 | -2.32 |

| Kentucky | 32.25 | 34.41 | -2.16 |

| Wyoming | 24.37 | 26.52 | -2.15 |

| Washington | 57.72 | 59.85 | -2.13 |

| Connecticut | 55.44 | 57.44 | -2.00 |

| Indiana | 38.58 | 40.34 | -1.77 |

| Nebraska | 38.00 | 39.38 | -1.38 |

| North Carolina | 47.03 | 48.30 | -1.27 |

| Iowa | 42.24 | 43.33 | -1.09 |

| Virginia | 51.94 | 52.85 | -0.91 |

| Montana | 39.03 | 39.64 | -0.60 |

| Georgia | 48.31 | 48.88 | -0.57 |

| New Mexico | 52.59 | 53.00 | -0.41 |

| Alabama | 34.47 | 34.55 | -0.08 |

| South Carolina | 40.90 | 40.94 | -0.03 |

| New Hampshire | 51.49 | 51.41 | 0.08 |

| Minnesota | 52.30 | 52.17 | 0.14 |

| Illinois | 54.80 | 54.62 | 0.18 |

| California | 60.93 | 60.73 | 0.20 |

| Louisiana | 39.07 | 38.81 | 0.26 |

| Rhode Island | 57.39 | 56.92 | 0.47 |

| Ohio | 44.80 | 44.27 | 0.53 |

| Nevada | 49.00 | 48.38 | 0.62 |

| Maryland | 64.09 | 63.31 | 0.78 |

| New York | 56.64 | 55.83 | 0.82 |

| Colorado | 56.61 | 55.69 | 0.92 |

| Arkansas | 35.24 | 34.30 | 0.94 |

| Wisconsin | 50.57 | 49.53 | 1.04 |

| New Jersey | 53.94 | 52.78 | 1.16 |

| Pennsylvania | 50.16 | 48.98 | 1.18 |

| Arizona | 48.33 | 47.15 | 1.18 |

| Massachusetts | 63.96 | 62.66 | 1.30 |

| Tennessee | 36.37 | 34.94 | 1.43 |

| Mississippi | 39.48 | 37.91 | 1.57 |

| Michigan | 51.20 | 49.30 | 1.90 |

| Texas | 44.97 | 42.98 | 1.99 |

| West Virginia | 30.49 | 28.49 | 2.00 |

| Maine | 55.67 | 53.48 | 2.19 |

| Florida | 45.61 | 43.38 | 2.23 |

| Missouri | 43.24 | 40.64 | 2.59 |

My average bias across all my state predictions was 0.74 percentage points for Trump, while among swing states, my average bias was 0.58 percentage points for Harris.

For error, my MSE across all states was 6.34, and my RMSE was 2.52 percentage points. This error was lower among swing states, where the MSE was 1.40 and the RMSE was 1.18. While this is still a pretty large MSE for swing states that can sometimes come down to fractions of percentage points, the fact that the error is less for my model that used polling speaks to the value that polling still holds, even though it can be biased. This will be discussed at more length later.

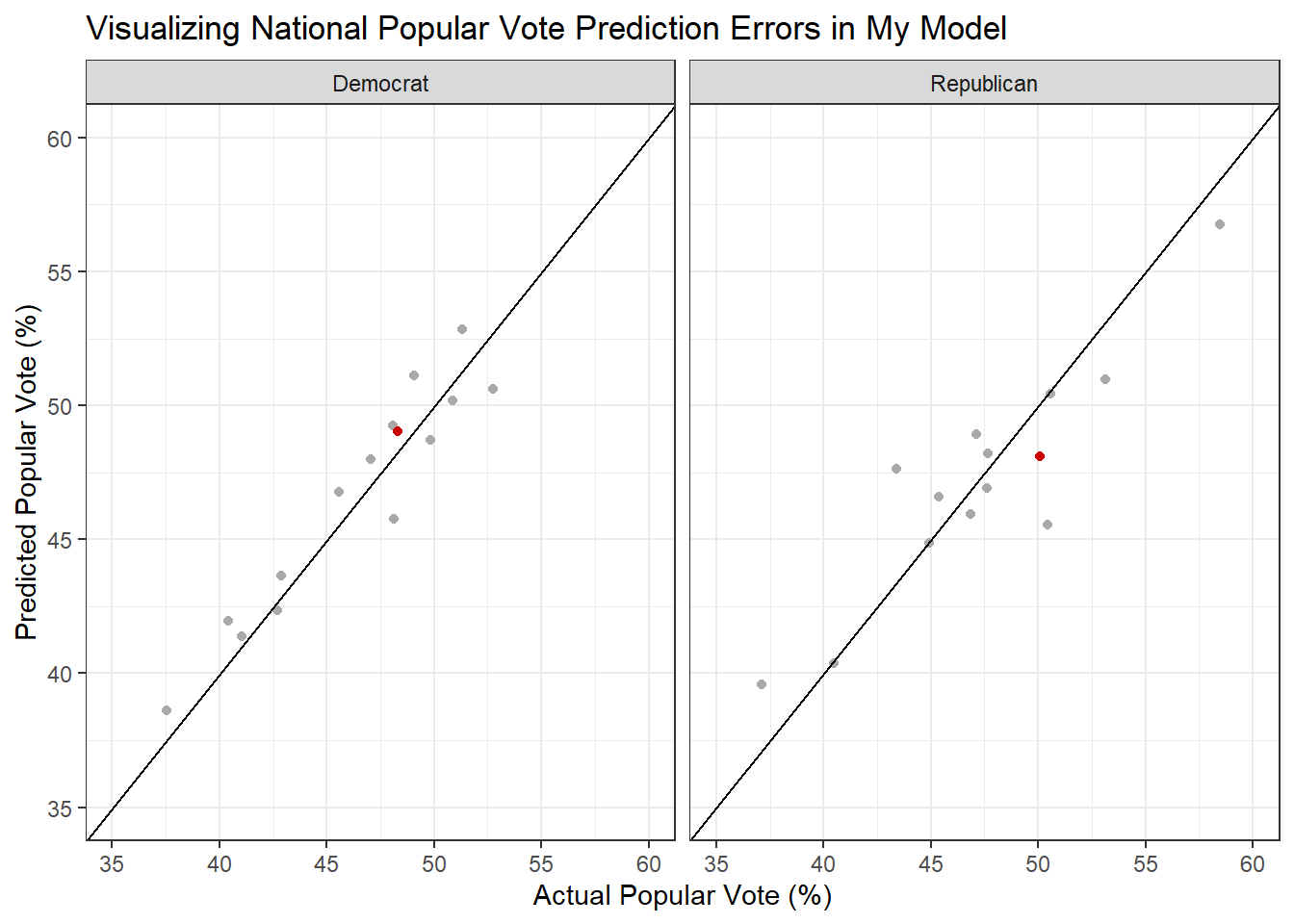

The graph below shows my national popular vote model’s predictions compared to the actual election results. The line through the center of each graph marks where a perfect prediction would fall. Observations above the line were predicted to get more vote share than they actually did, while observations below the line were predicted to get less. The red dot is 2024.

All things considered, I’m actually really happy with my national popular vote model. My predictions were not all that far off, and visually my prediction was actually closer in 2024 than several of the points the model was trained on, which is a good sign for it’s generalizability to future years. One thing to note is that my model seems to predict Democratic vote share more cleanly than Republican vote share on average, even though it was trained on training data from both parties.

What went wrong? A few too many theories

Below is a list of reasons, some more abstract than others, that I think my model or models that others made may have been off this election cycle:

The weighting of polls and their lean toward Harris. My state-level predictions used two models, one that incorporated polls and one that did not. In some ways, it gives me an imperfect counter factual because I can see that my prediction error increases when polls are not factored into predictions. That said, the polls this election cycle did lean toward Harris. FiveThirtyEight’s aggregates showed Harris up in the national popular vote for the entire election cycle and up in Michigan and Wisconsin since August. Pennsylvania and Nevada were essentially toss ups, while Georgia, North Carolina and Arizona were more clearly for Trump. In reality, Trump won both toss up states by at least two percentage points and Michigan and Wisconsin by about 1 percentage point. Polling is imperfect, as is forecasting, and pollsters have struggled with underestimating Trump in every election he has been in thus far. A hypothetical test we could run to look at the impact of some aspects of polling error, specifically how much error was induced by the weights pollsters applied to their samples, would be to compare the difference between the actual outcome and the polled outcome for the weighted polls and those same polls if unweighted.

The unpopularity of the Biden administration was not properly accounted for in my models. I think the polls maybe overestimated the enthusiasm and support behind Harris, and my model did not balance that out by incorporating more economic factors or approval ratings. It’s hard to imagine a test that could account for the role that Biden’s unpopularity played in Harris’ campaign. There is some preliminary evidence of this in key swing states like Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan and Nevada, which all voted Trump for president, but blue for the Senate. This could imply that Harris (or Biden’s shadow) was the problem more than Democratic policies. I could imagine too a data analysis project that compares Harris vote share between locations where Biden was allowed on the campaign trail and those where he was not to see if his presence had an actual negative impact, although there would definitely be a lot of confounding factors in that analysis because it wasn’t randomized.

Bias in including lagged national popular vote. This election is the first time the Republican nominee has won the national popular vote for twenty years. Because this variable is one of only eight predictors that LASSO selected for my popular vote model, there may have been a Democratic skew, especially considering that five of the other variables were polling, which was also skewed towards Harris this election. That said, while I think this may have affected my model early on, as we approached the election and I added more polls, the predicted national popular vote margin for Harris continued to shrink, which brought my prediction pretty close to the actual outcome. One test I could run to see if this impacted my model results would be to try taking it out and see how that changes my prediction. I could also try bootstrapping using a randomly selected, feasible value for national popular vote to get a range of possible predictions for Harris vote share in 2024, and then see how many times I still would’ve predicted a Harris win.

My model, and probably many others, assumed a normal campaign for Harris and didn’t try to account for the effects of Biden’s late game dropout. My working theory is that it impacted her campaign in a couple of key ways. First, I think that the shorter campaign and lack of a primary season for Harris limited her ability to campaign in Democratic stronghold states like California and New York. Although she could safely expect to win these states, I think the lack of time to hold campaign events there may have been one of the mechanisms behind her losing the national popular vote. Second, I think her campaign of not much longer than three months just wasn’t able to compete in terms of name recognition or information, which could have contributed to some of the margins in swing states. I’m not sure how much precedent there is for a late drop out like occurred this election, but I could try incorporating a variable for campaign length or a variable for campaign events in stronghold states into my national popular vote model to see if that would change my predictions. Additionally, some exploratory data analysis on the correlation between the number of campaign events in stronghold states and the national popular vote or state turnout might provide preliminary evidence for that theory.

Harris is a woman and unfortunately that probably did lose her support. I think I went into model creation for this class really optimistic. It never would have occurred to me that something like that could sink her campaign. It’s very possible that my understanding of the situation is overfitted because, in my memory, there have only been two female candidates for president and they both lost to Trump. That said, looking at some of the demographic swings in the CNN exit polls and Harvard Youth Poll results, there is definitely a gender gap. The gender gap in support for the Democratic party candidate among young voters doubled from the spring to fall (Biden to Harris). The gender gap among Latino voters was massive, with Harris losing Latino men by 12 percentage points, a demographic that Biden won by 23 percentage points in 2020 and winning women by 22 percentage points. For black voters, there was a 28 percentage point gap between men and women in support for Harris. This is a hard one to test because we can’t observe the counter factual of what would’ve happened if Harris had been a man, but correlative analysis on the gender gap could provide more evidence for it.

Maybe the assassination attempts actually did significantly impact the election, but their impact was masked by the weight of the polls. This would be really hard to prove in any sort of substantial way because we definitely cannot observe that counter factual. We see some evidence of the Trump upward swing in the polls following his assassination attempt in July, but they end up largely masked by Biden’s dropout. It would be interesting to see if this trend is any different using unweighted polls or unweighted polling averages.

All that said, while I had fun coming up with a lot of theories, I think the biggest issue with my models was not accounting properly for the fundamentals, which is what the next section proposes changes to address.

Here’s What I Would Change For Next Time

I would use ensembling to combine predictions based on fundamentals and predictions based on the polls. I expect that a lot of people in the class are questioning their model’s reliance on polls right now, and whether they should even be included. I think my model for Electoral College predictions offers an especially interesting perspective because there were actually several states for which my predictions did not factor in polls at all, and these states were usually the states with the largest prediction errors. Luckily, these states were usually also safe states (which is why they didn’t have much polling), so errors in vote margin during the prediction process did not have serious consequences for my overall predictions. However, these larger errors convince me to not give up incorporating polling altogether, just to down weight them more to account for the true influence of fundamentals.

I would include interaction effects in a future model. I suspect that the economic factors would have had more predictive power if they were specified to have a relationship with incumbency. I believe the same would be true for approval rating. I think including interaction effects like these may have given my model the opportunity to account for the influence of the Biden Administration on Harris’ ultimate loss, and also to balance out the overall slant of the polls.

I would regularize the values of my predictive variables before feeding them into my national popular vote model so that variables with larger values wouldn’t be more likely to drown out variables with smaller scales. I could then use LASSO for variable selection and feed the variables it selected back into a basic, linear model based on the original data to keep important variables that maybe didn’t have an effect so physically large as others.