This week, we discussed incumbency, federal spending and expert opinions as they relate to election forecasting.

How does incumbency influence presidential races?

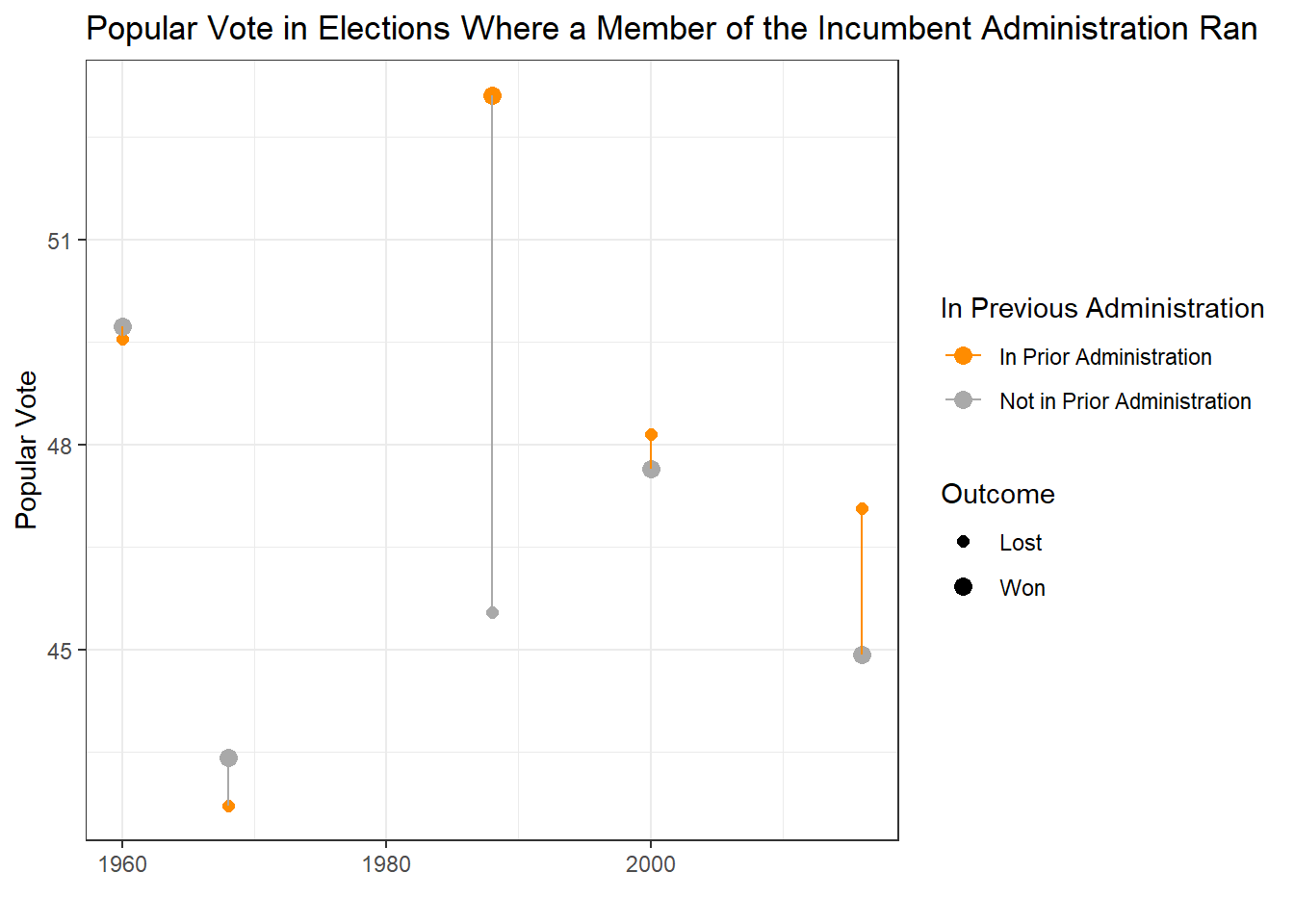

The question of how incumbency will play into the 2024 election is a complicated one. Historically, the advantage or disadvantage of running as a presidential candidate for the incumbent party, but not the incumbent president has been rather unclear. To narrow in on Harris’ situation a little further, the graph below shows the elections where a member of the incumbent administration has run for president, but not the incumbent themselves.

We can see in the graph that since 1948, this has only happened 5 times. In 4/5, the candidate from the incumbent administration has lost the electoral college. Interestingly, 3/5 have won the popular vote. Additionally, elections involving candidates from incumbent administrations have often been very close.

Kamala Harris’ case is a little different than the standard one. She is runnning as a member of the incumbent administration (the VP), but in the wake of a one-term incumbent president stepping down. 6 other US Presidents have made the decision to not run for a second term: Lyndon B. Johnson, James K. Polk, James Buchanan, Rutherford B. Hayes, Calvin Coolidge, Harry S. Truman and Theodore Roosevelt (although he later changed his mind and ran in the following election). 4 of those presidents’ parties lost re-election (Polk, Buchanan, Truman and LBJ), while 3 won (Hayes, Roosevelt and Coolidge). There is no clear advantage or disadvantage in this alone. The most recent example of this situation was in 1968, when Hubert Humphrey (the incumbent VP) lost to Richard Nixon following LBJ’s stepping down.

Similarly, it is uncommon for a former president to lose re-election and actually be a viable candidate in the next election. Only six others tried and only one, Grover Cleveland, succeeded. Ulysses S. Grant and Herbert Hoover were both unsuccessful in gaining their party’s nomination and Martin Van Buren, Millard Fillmore, and Theodore Roosevelt ran unsuccessfully as third party candidates. It is unclear whether there is any sort of advantage or disadvantage in the case of Trump because, usually, the candidate’s party alone presents enough of a barrier to a former president seeking non-consecutive terms. That being said, the one time a former president did secure their party’s official nomination, they won the election.

Given all of this, I don’t really believe that either candidate will have much of an incumbency advantage. I would anticipate that Trump gains no advantage or disadvantage based on his prior term as president. Similarly, the jury is still out on whether Harris’ role as VP in the Biden administration will help or hurt her. In this election, I think both partisan identification and administration favorability would be more predictive than incumbency.

What is the value of expert opinions in election forecasts?

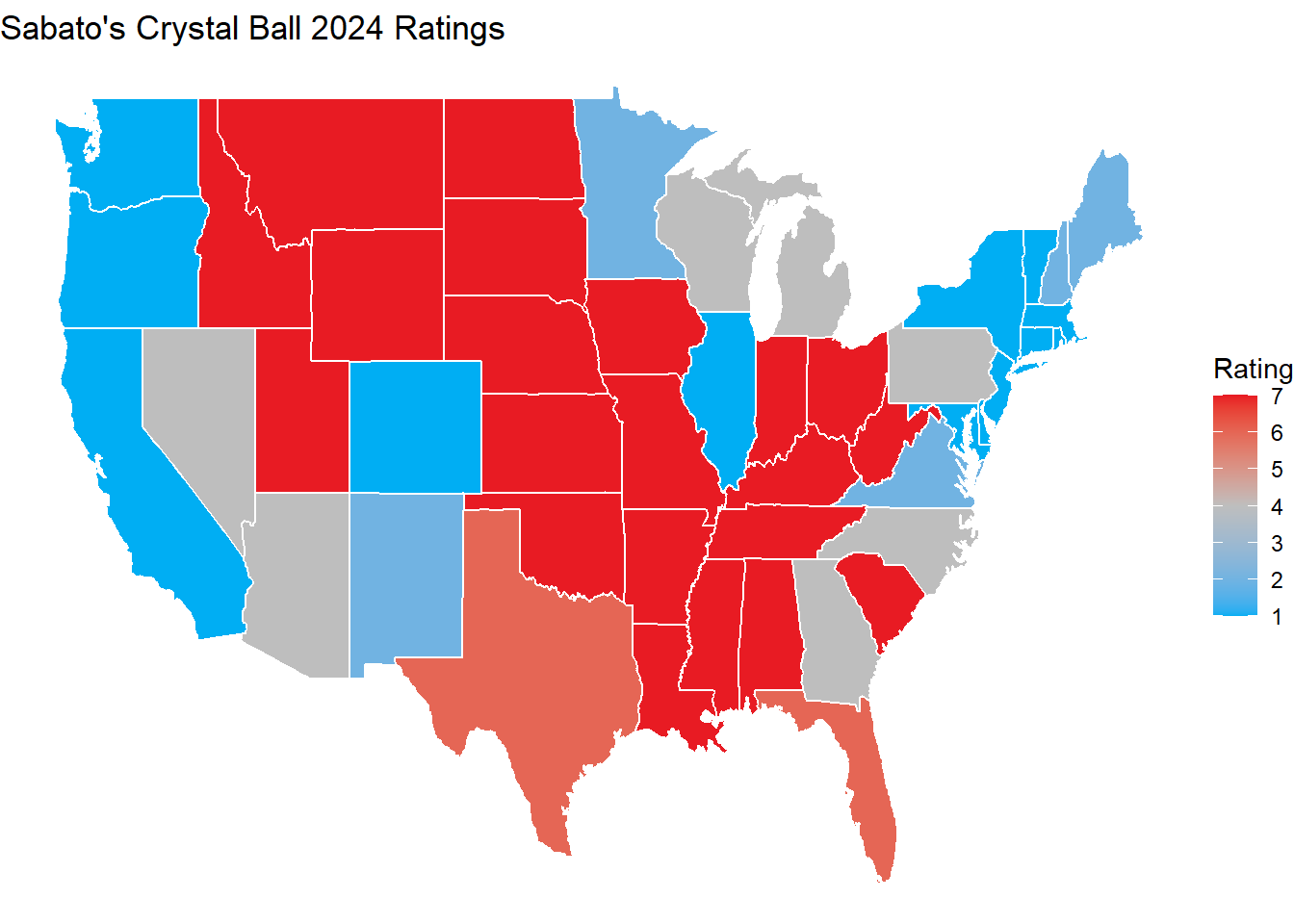

In class this week, we also discussed the value of expert opinions and their accuracy in predicting elections. Based on our discussions, I don’t anticipate using expert opinions very much in my own forecast, primarily because they do not include an estimate of popular vote. While expert opinions are typically accurate, they are too wishy-washy for my personal taste (yes, that is the technical term). Most expert opinions, operate on a scale of 5-7 points that ranks strong and less strong for each party or a toss up. These categories are, in my opinion, much too broad to be helpful as I attempt to predict state-level popular vote share. However, we did discuss that expert opinions may be valuable in helping to decide which states to build more complicated models for.

The map below shows Sabato’s Crystal Ball ratings for the 2024 election cycle.

Based on that map, it would follow that I should spend the most time on predictions for Nevada, Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Georgia and North Carolina.

Incorporating Incumbency into my Predictions

In past weeks, I have done some state-level modeling, but this week I really want to take the time to work more comprehensively on my state-level predictions. So far, we have discussed past voting patterns, the economy, weekly polling averages, incumbency, and expert ratings as possible predictive variables to include in forecasting models. I do not include expert ratings in my predictions for the reasons described above.

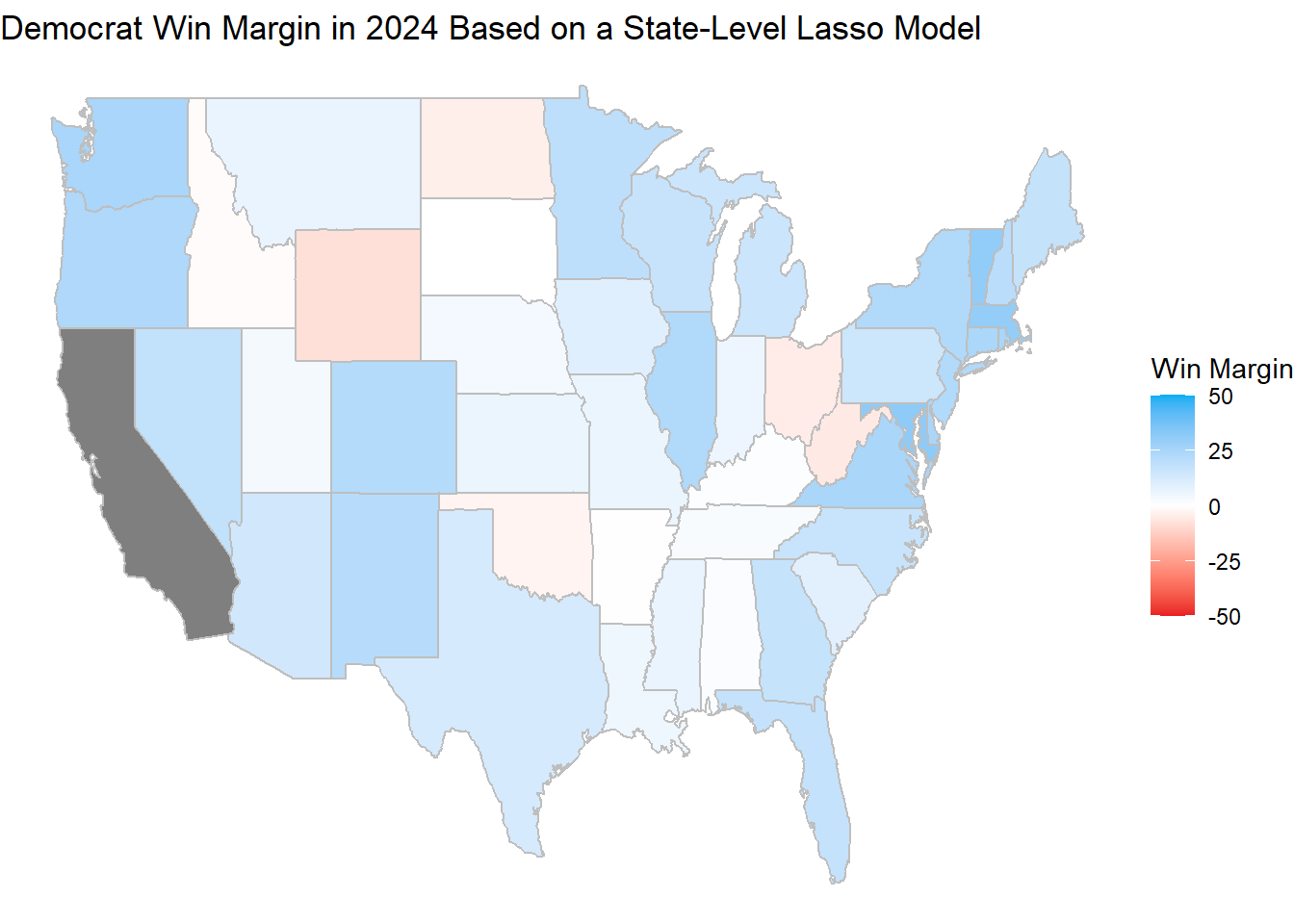

In my model, I took a shot at imputations for missing values and, as can be seen in the map below, I likely made some poor decisions. Namely, for missing state polling values in the year 2024, I imputed the average polling score for that week in the state’s geographical region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). There is definitely more variety to a state’s polling averages than just what is common in their region. Geographical regions alone were not a sound imputation technique, and I think it skewed my model in the direction of Kamala Harris. We can see that my model predicts some states that are typically solid red as approximately toss-ups in 2024. In the future, I hope to be able to perform something similar, but maybe by blocking states together based on voting history, as opposed to geographic proximity. Alternatively, I could weight recent voting patterns heavier in my model.