Historic Accuracy of Polls

Poll averages seem like an intuitive way to predict elections - if I walk around and ask everyone who they are going to vote for, I should get a pretty good idea of how many people are voting for each candidate. Polls are a valuable prediction tool for election forecasts. However, not all weeks of polling are the same. Historically, polls become more accurate as the election approaches, often converging near the correct value within a week or so of the election. Several theories attempt to explain this, including the “enlightened preferences” theory expressed by Andrew Gelman and Gary King in their article Why are American Presidential Election Campaign Polls so Variable When Votes are so Predictable?, which posits that as the election draws nearer, the campaigns of each candidate draw attention to and inform the public about the fundamentals, which fairly accurately predict popular vote outcomes.

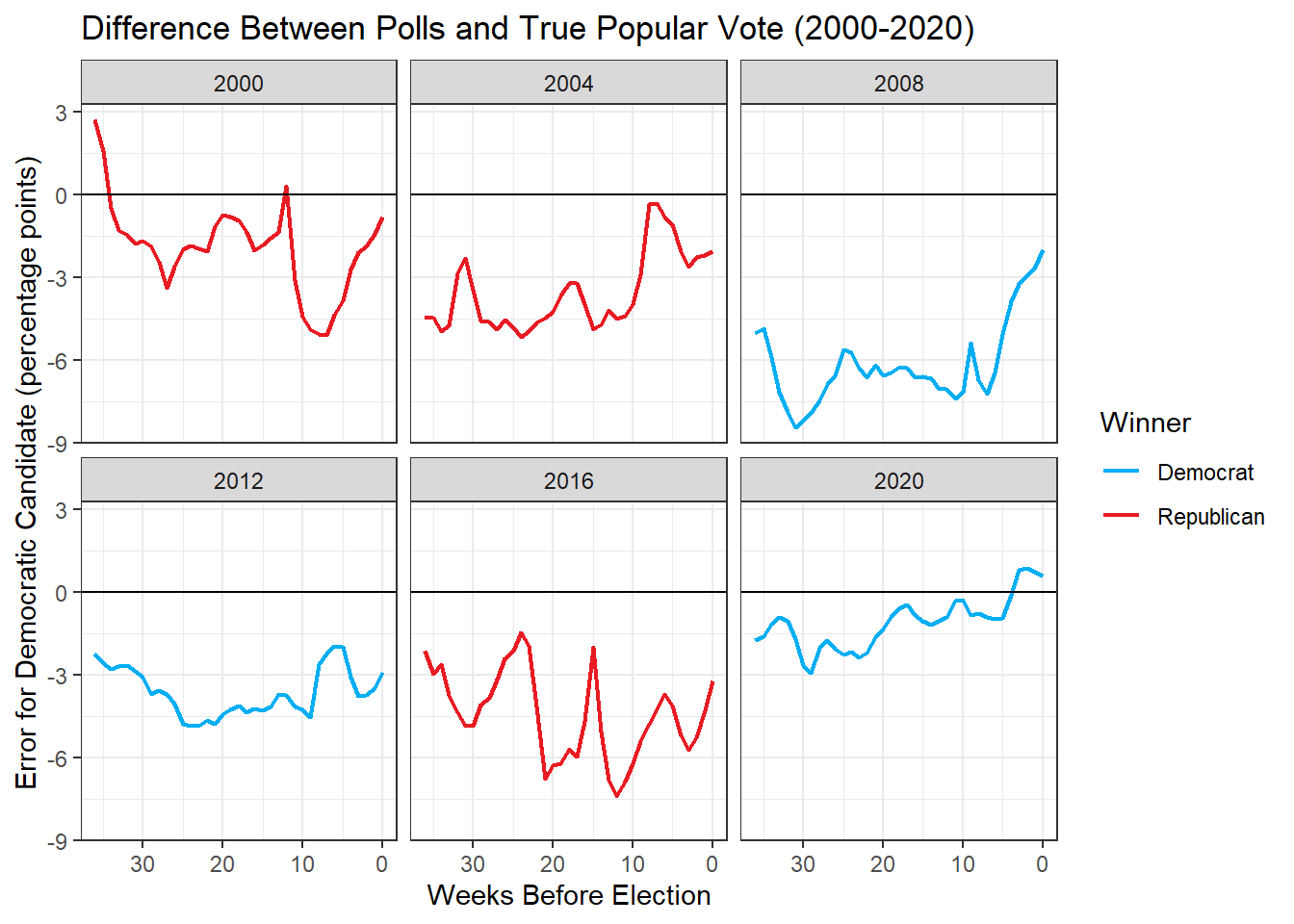

The following graph shows differences between polls and actual popular vote over the thirty-six weeks leading up the election from 2000-2020.

Interpreting this graph, a perfect poll prediction would be at the line y = 0, which marks no difference between the poll predictions and the true popular vote. A difference above the line means that the winner was over-predicted to win and below marks an under-prediction. We can see that, in general, poll estimates are approaching zero as the election draws near. Another trend is that winners are often under-predicted. Notably, many polls, especially in recent years are also fairly accurate to begin with, with starting measures ending up very close to the end measure and variation in the middle. One reason for this may be that, because Americans are increasingly partisan, their views may change less over the course of the campaign.

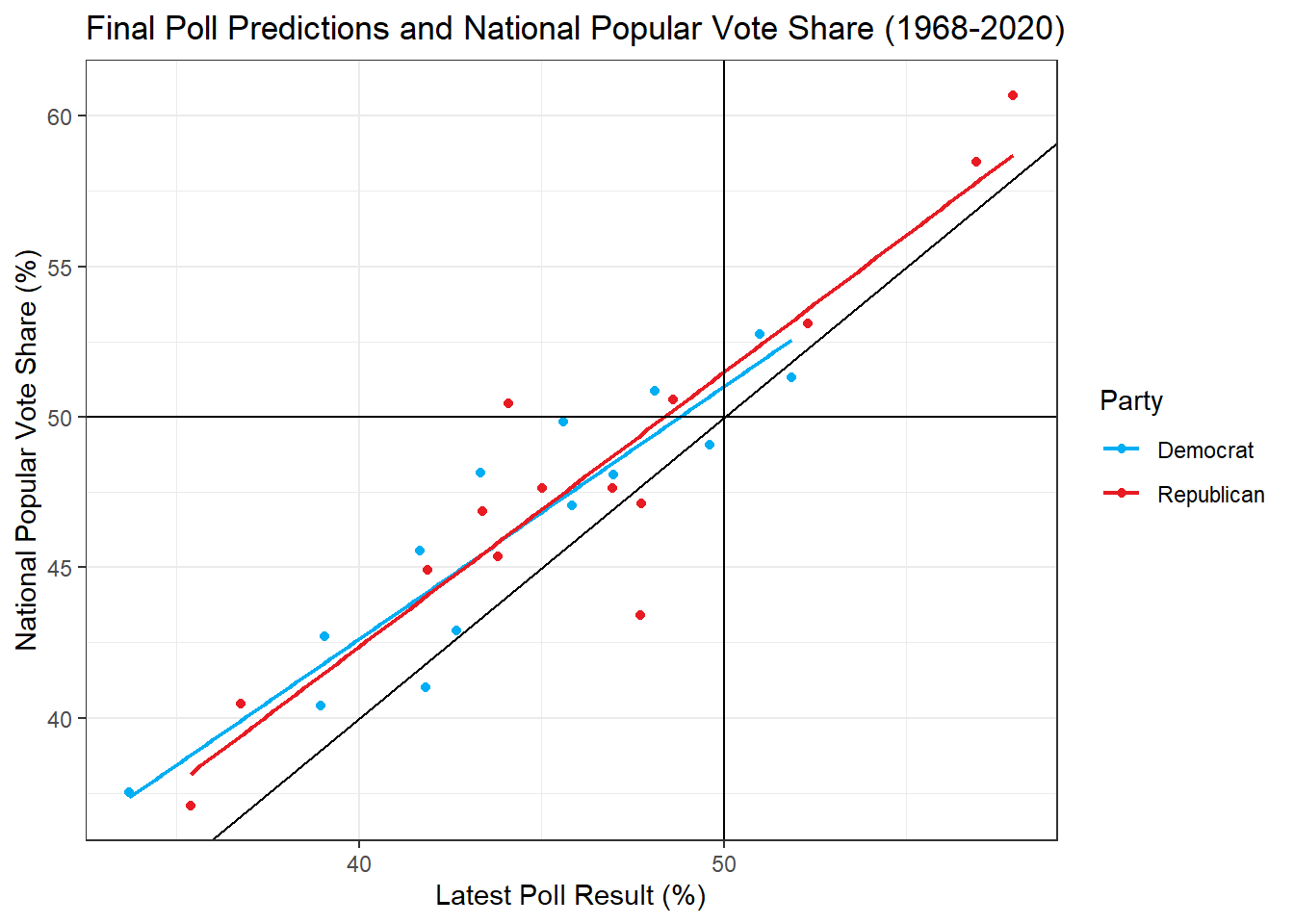

Interpreting this graph, a perfect poll prediction would be at the line y = 0, which marks no difference between the poll predictions and the true popular vote. A difference above the line means that the winner was over-predicted to win and below marks an under-prediction. We can see that, in general, poll estimates are approaching zero as the election draws near. Another trend is that winners are often under-predicted. Notably, many polls, especially in recent years are also fairly accurate to begin with, with starting measures ending up very close to the end measure and variation in the middle. One reason for this may be that, because Americans are increasingly partisan, their views may change less over the course of the campaign.The following graph visualizes the final poll prediction prior to the election and it’s correlation with the actual result.

In general, the final poll result is very similar to the true election popular vote. This graph also shows the tendency of polls to under-predict the true popular vote, which may be due to the influence of third parties. Perhaps, voters who are questioned by pollsters are more likely to say they will be voting for a third party candidate than to actually do it.

In general, the final poll result is very similar to the true election popular vote. This graph also shows the tendency of polls to under-predict the true popular vote, which may be due to the influence of third parties. Perhaps, voters who are questioned by pollsters are more likely to say they will be voting for a third party candidate than to actually do it.2024 Polls Thus Far

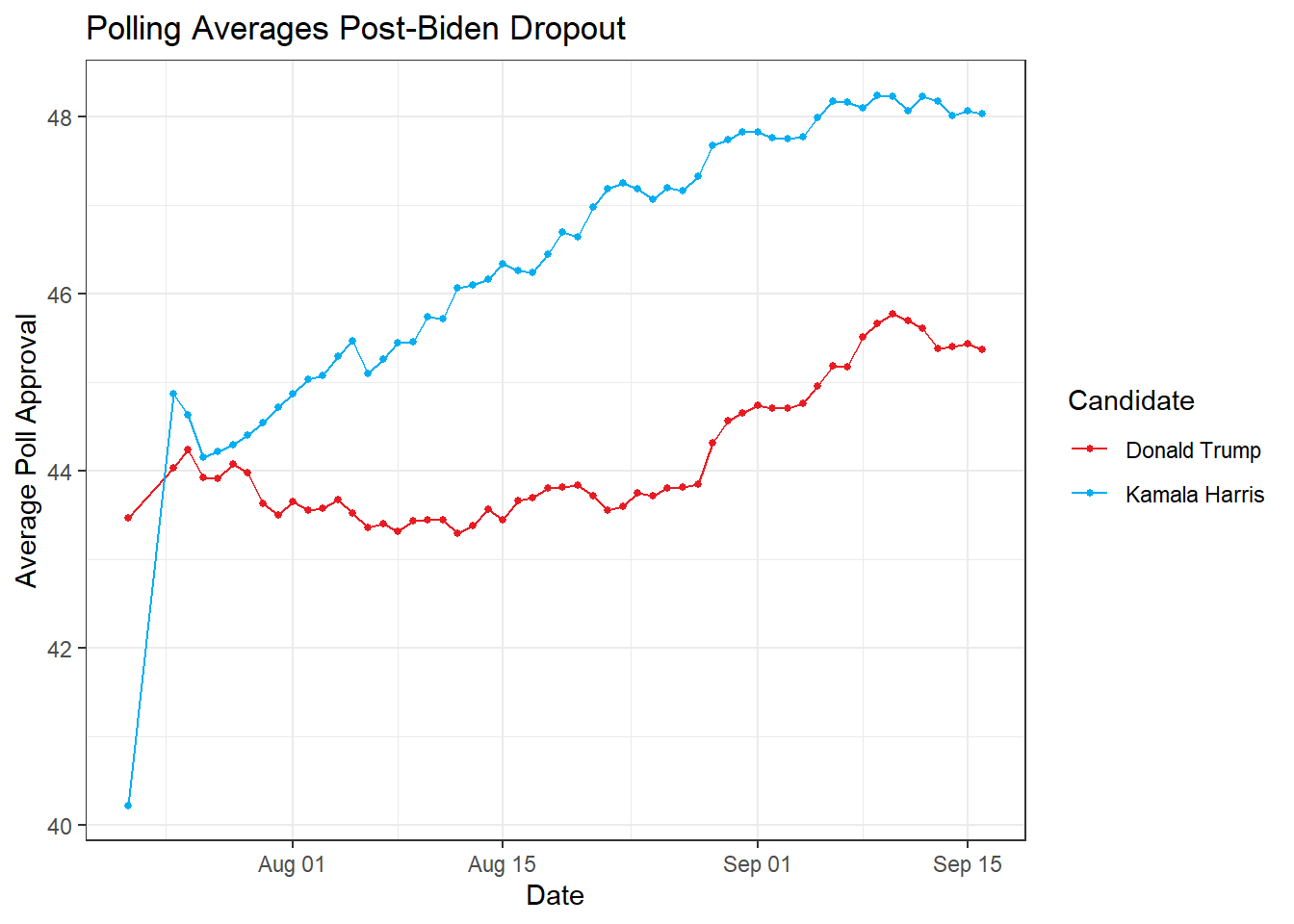

In predicting the 2024 election, we in some ways have less polling data to work with, owing to Biden’s late-in-the-game dropout.

Since Biden dropped out of the race, poll numbers for the Democratic Party have improved greatly, with Kamala Harris polling on average above Donald Trump.

State and National Level 2024 Predictions

Taking a deep dive into predicting 2024 outcomes using polling data, we historically have polling data from 30 weeks prior to the start of an election until the week of.

Using every week in that range from week 30 to week 0 to predict the election outcome would utilize more predictive variables than outcomes to test them on. For this reason, we must take steps to remove unnecessary predictive variables from the analysis and keep only those that matter most.

Trying three different methods: ridge, lasso and elastic net, the lasso method had the lowest mean squared error, although the elastic net method was a very close second. I opt to use lasso for the sake of model simplicity, since lasso has less variables by nature of shrinking less important variables entirely to zero.

## s1

## [1,] 51.50739

The lasso model predicts that Kamala Harris will win 51.51% of the popular vote, while Donald Trump and other candidates win the remaining 48.49%.

Combining Fundamental and Polling Data

As I have explored in prior blog posts, it doesn’t always make sense to predict on only one factor at a time while ignoring others that may be important.

A lasso model based solely on fundamentals would predict Kamala Harris to beat Donald Trump in the two party popular vote 50.42% to 49.58%. Further, neither Lasso nor Elastic Net actually chose any of the fundamental variables to predict on. This is definitely not a model that we want to be predicting on.

## s1

## [1,] 50.4831

## [2,] 47.9374

Predicting on fundamentals and polling combined, both Lasso and Elastic Net models predict Kamala Harris to win approximately 50.5% of the popular vote to Trump’s 48%. However they differ in their methods. Lasso used only week 30 polls, while Elastic Net added week 10 polls and the popular vote from the two prior elections in.

Overall, I don’t love most of the models explored in this blog post. I want to be able to intuitively explain my final model and the variables that are kept or discarded. I expect that this will become easier as the election approaches and I am able to use weekly polling data that is closer to the election, which is historically more predictive. I look forward to further digging into the details of these models, building models using ensemble techniques and applying them to state-level prediction in future weeks.

What Do Forecasters Do?

In preparation for class this week, we read about both the Silver (2020 presidential and prior) and Morris models (2024 onward) from 538.

Both models broadly follow three steps: developing average polling models, combining them with fundamental models, and incorporating uncertainty and simulating the election.

Silver’s polls are weighted higher based on both their sample size and pollster rating. The polling averages are a combination of two methods, a more conservative weighted average and an aggressive trend line, which is weighted higher as the election gets nearer. Polls are further adjusted based on likely voters, polling house biases and timeline adjustments for poll age. They are also adjusted to mitigate the effects of short-lived historical bumps, for example national conventions or debates.

The model then adds in the fundamentals, which incorporates demographics, historical voting patterns, economic conditions and incumbency. They assign a partisan lean to states based on past voting data, very similar to what we did in the first week, weighting the prior election at 0.75 and the one before that at 0.25. They further modify this lean to account for home state advantages, states with more swing voters (which may respond more to national trends), and how easy it is to vote in a state (the model operated under the belief that stricter restrictions are more beneficial to Republican candidates in 2020, but is cancelling out the advantage in 2024). In the end, the model creates an ensemble forecast, combining rigid adherence to the original partisan lean, a weighted average of nearly 200 different demographic regression combinations, and a regional model. This is used to help balance out predictions in states that do not have as much available polling data. The model also incorporates the economy, specifically jobs, spending, income, manufacturing, inflation and the stock market. Silver places relatively little weight on the economic fundamentals model and uses it early in the election while the polls settle down, before slowly removing its influence (which is zero by election day).

Finally, Silver accounts for uncertainty and simulates the election thousands of times to calculate the probability of winning for each candidate. The uncertainty index he uses combines undecided voters, third party voters, polling volatility, the difference between polling based and fundamentals models, economic volatility and news (more uncertainty) and polarization and volume of polls (less uncertainty).

The Morris model is not so different. In general, the approach the models take is very similar. I wanted to highlight just a few key differences. First is the way sample size is weighted in polling averages - the Morris model caps surveys at 1500 respondents so that super large polls don’t sway the model more than they should. The Morris model also includes more factors in the economic predictions. Their factors include those from the Silver model, plus five new: average real wages, housing construction, real sales for manufacturing and trade goods, U Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment, and real personal income per state. This is done with the intent of incorporating more subjective measures into the analysis, versus only the standard objective ones.

Another factor the Morris model stresses is the impact of polarization on traditional election forecasting methods. To account for it, they down weight both the economic conditions and presidential approval for polarized elections. Further, the Morris model never completely phases out the fundamentals, whereas Silver phases them out entirely by election day.

I tend to prefer Morris’ model for a few reasons. First, as I have discussed relatively frequently in recent blog posts, I believe polarization to fundamentally change the standard forecasting models. I’m partial to the partisan weighted fundamentals approach that Morris takes. Second, I like that it doesn’t phase out the fundamentals completely by Election Day. I think the fundamentals are weak on their own, but they definitely still are an asset to forecasting models up until election day. Third, I would hypothesize that consumer economic perception may be an important and distinct influence not captured by standard economic variables, so I like the model incorporating variables that attempt to capture it. Finally, somewhat superficially, prefer Morris’ model because it was described in a more understandable way for the average reader and I think transparency is one mark of a good model.